AI and I Part 1: The Robot Ate My Blog

Welcome to the first in a 2-part series dealing with what will almost certainly come to be seen as a defining feature of our age: the rise of artificial intelligence. While AI is hardly a bolt from the blue – the term was coined in 1955 – the release of ChatGPT by Open AI just under a year ago has catapulted it from the realm of the esoteric to the everyday. Not only is this immense power now at the fingertips of everyone, but everyone is now at the fingertips of this immense power.

The Write Stuff

As the title implies, Part 1 is about how AI directly effects my work as a professional writer and content creator. For the TL;DR contingent, there are two conclusions I reach. 1. AI is a useful tool that can augment, complement and optimise my work. It is not a rival intelligence that has sinister motives to replace me. Yet. 2. Humans are fundamentally social creatures who share a deep and unconscious bond. This is reflected in the choices they make as consumers.

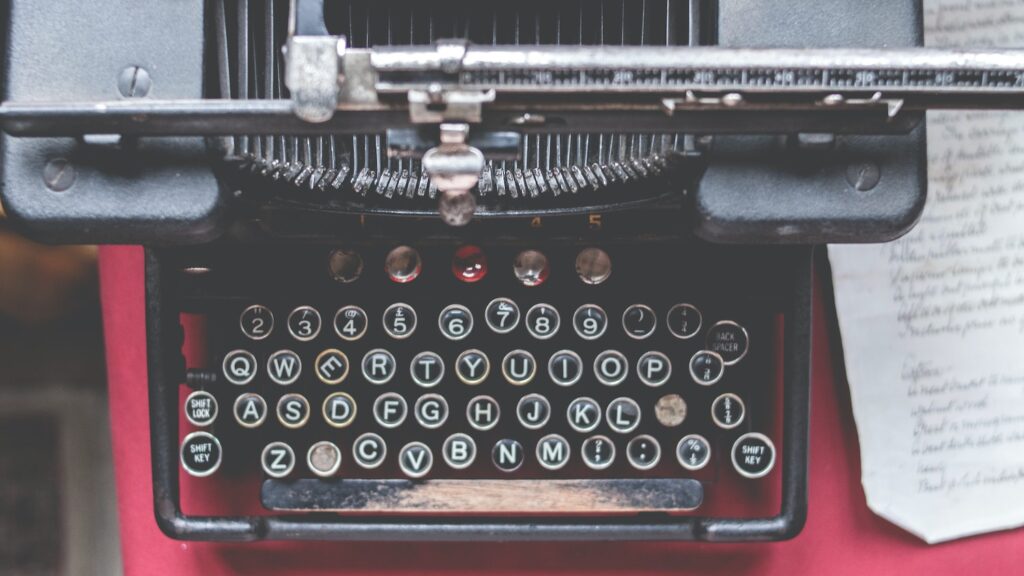

At this visceral level, a human being will have far greater appreciation for something that has been lovingly crafted by the hands of a fellow human than that which has been generated by a soulless piece of tech, no matter how human-like it may appear. As a result, I position myself as an “artisanal blogger” and offer content that has been crafted with the kind of love and care only a flesh-and-blood human is genuinely capable of. Doing so will hopefully enhance your experience of reading it.

Looking ahead, Part 2 will offer a more panoramic reflection upon how the rise of AI is likely to affect the wider world of work.

Paradigm Shift

It’s safe to say that most of us are aware that the advent of artificial intelligence marks a far more fundamental change in the very fabric of our lives than any other recent tech innovation. This isn’t a dazzling VR headset or a clever app that monitors our breathing patterns while we sleep. Even OpenAI, the research laboratory that opened Pandora’s Box with the release of ChatGPT, refers to it as “superintelligence”, which is defined as “a form of AI that is capable of surpassing human intelligence by manifesting cognitive skills and developing thinking skills of its own.”

In fact, in their blog, OpenAI frankly state: “Superintelligence will be the most impactful technology humanity has ever invented, and could help us solve many of the world’s most important problems. But the vast power of superintelligence could also be very dangerous, and could lead to the disempowerment of humanity or even human extinction.”

This is why OpenAI are committed to what they call “superalignment”, (does everything suddenly have to contain the prefix “super”?) in which humanity and technology complement one other instead of competing with each other.

If the company that is the most prominent player in the AI field readily admits that they have created something that could lead to human extinction, it’s no wonder they want their creation to play nicely with us. As far back as 1921, Norwegian Nobel laureate Christian Louis Lange observed that “technology is a useful servant, but a dangerous master”. It goes without saying that the optimal scenario is that of the human body wagging the technology tail and not the other way around.

In fact, a body no less authoritative than the World Economic Forum cites a key component of the Fourth Industrial Revolution as “the ability to harness converging technologies in order to create an inclusive, human-centred future.” Yet even the WEF, in spite of its optimistic vision of “technology in the service of humanity”, acknowledges that these extraordinary technological advances are “merging the physical, digital and biological worlds in ways that create both huge promise and potential peril.” The unspoken fear remains implied: what if technology harnesses humanity and not the other way around?

And this is not even the realm of the deranged doomsayers: humans have a proven track record of setting in motion forces we then struggle to contain. “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” said theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer, quoting from the Bhagavad Gita when the first nuclear bomb mushroomed across the New Mexico sky on a cold June day in 1945. We certainly possessed the ingenuity required to split the atom, but once the genie was out the bottle it had no desire to get back in. To paraphrase Winston Churchill: “We shape our technologies, thereafter they shape us.”

Be that as it may, we’re not here to torment ourselves with apocalyptic visions of the robot uprising. Besides, if the superintelligence “decides to treat us like we treat chickens”, as a British software engineer recently put it, there’s precious little we can do about it. We’ve all seen The Matrix and it doesn’t end well for us humans. The tech horse has bolted and no amount of slamming of the barn door will return it to the confines of its stable.

Let’s Chat

For the purpose of this piece, we’re focusing on the most well-known type of AI that powers headline-hogging applications such as ChatGPT. The latter is a form of Generative AI known as an LLM (large language model) which is capable of performing, with tremendous speed and precision, just about any natural language processing (NLP) task asked of it. It can generate any kind of text, code, images, video, audio, 3D models, mathematical procedures and more that the user asks of it, hence the term “generative”. In fact, that’s what the “G” in “GPT” stands for: Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer.

Although there are myriad forms of highly specialised AI programmes, the large majority of them fall under the “generative” category. After all, their job is to generate solutions to problems infinitely more quickly, precisely and effectively than humans ever could. For example, Canadian scientists recently trained an AI to create a powerful new antibiotic capable of killing a previously antibiotic-resistant bacterium. The AI was fed vast amounts of training data which allowed it to do the kind of modelling, synthesising and simulated testing that generated a result that would have taken humans hundreds of years to obtain.

“Training data” is essentially what AI is all about. If you feed the machine enough examples of what you want it to produce, it shall do so. If you feed an AI, let’s say, the screenplay of every rom-com every written and instruct it to write a rom-com about literally anything (e.g. “dented jalopy falls in love with luxury supercar”) it will. The only limiting factor here is money. If you wanted to follow through on the above example, you would need to spend astonishing sums to amass the computational power to generate the result.

This leads to one of the darker shadows cast by the rise of AI: in the future, the world will quite conceivably not be run by governments but by tech corporations (Skynet, anyone?) who will be the only players with the resources to win the AI arms race. It’s somewhat analogous to the atom bomb – in theory anyone can make one, but only entities with unlimited budgets can afford the wherewithal to actually produce them.

And that’s not even too wild a supposition: Microsoft has invested heavily in Open AI; Google in Bard; Meta in LLaMA and Elon Musk has just launched his own brainchild named xAI. (Not to be confused with his actual child, X Æ A-12.) You don’t need to be a Marxist economist to fathom that those in possession of the means of production wield disproportionate amounts of power and control. The code for LLaMA might be open source, but unless you have a veritable armada of supercomputers, your plans to take over the world might require some refinement.

But, before we veer too far off course, let’s return to the point of this article. What does AI have to do with my blog? Well, everything really. In previous industrial revolutions, the emphasis was upon the mechanical: the labour replaced by machines was by and large manual. For example, when the car assembly plant became automated, robots took over the jobs of humans. However, in the 4th Industrial Revolution, the robots can now do the intellectual work of humans.

The Real Deal

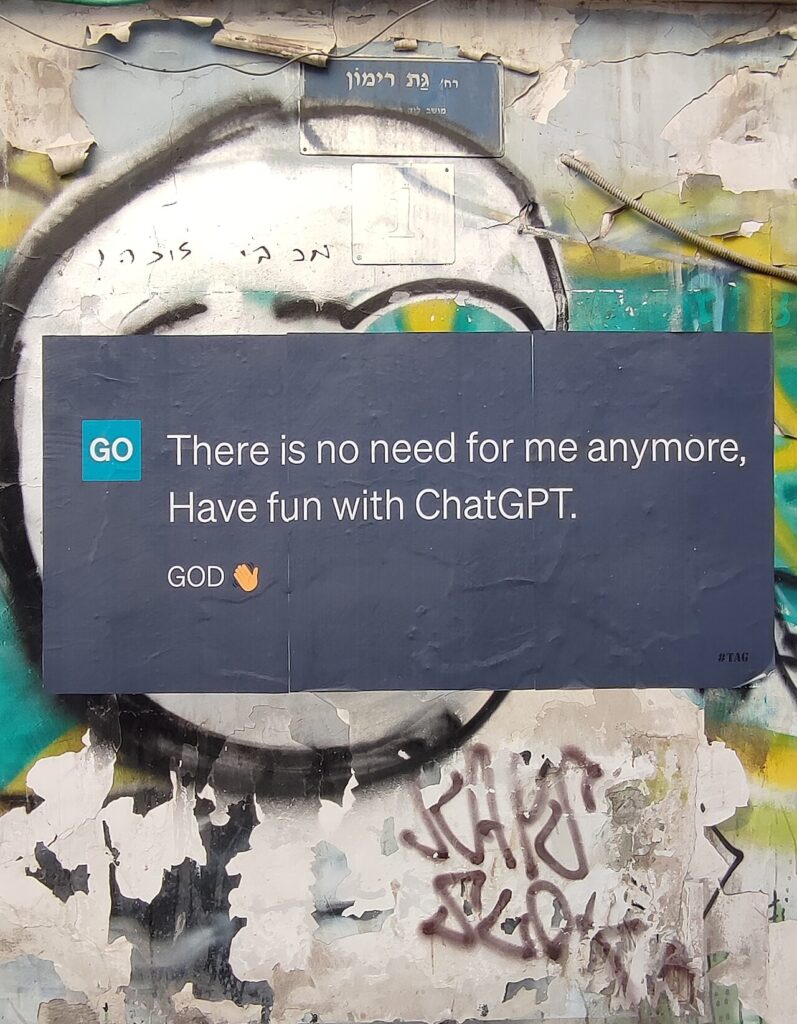

Which brings me to the question implied in the title: how do you know this blog wasn’t written by a robot? The simple answer is that you don’t. I could have instructed ChatGPT to generate an article about how AI can write articles just as well as any human can and something along these lines could well have been the result. So you’ll just have to take my word for it that human hands scurried across a computer keyboard to assemble the words that comprise these sentences.

On to the second question: Do you care if this article was written by an AI? I would very much like to think so. Advanced technology we can barely comprehend pervades our everyday lives so extensively, why not let it run rampant creating the content we consume? The cars we drive are made in factories run on AI, and pretty soon AI will be driving them for us too. The clothes we’re wearing, much of the food we eat and the tools we communicate with are all the result of industrial processes in which AI plays a central role.

However, all of the above relates to the role of AI in production but neglects to look at the crucial elements of cognitive human psychology at play when it comes to the consumption side of the equation.

The Crafting Hand

A deep-seated trait of human consciousness is the separation between the aesthetic, spiritual and sensual (art, literature, music, film) and the mechanical, industrial and technical (science, technology, manufacturing). Sure, let the robot build my car, my cellphone, my television and the miracle life-saving drugs but don’t let it write the novels, direct the films or paint the paintings. That’s where the human connection remains fundamental, integral and inviolable. We call it craftsmanship and artisanry and we have tremendous love and respect for those material elements that are built lovingly by hand.

The visceral connection between items of value produced by humans and those consumed by humans is a tradition stretching back thousands of years. Who wouldn’t prefer the handmade pastry to a slab of industrial polony? The handcrafted leather handbag to the mass-produced plastic holdall flung off a production line by the millions?

According to Newton’s Third Law, for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. This applies just as well to culture and society as it does to physics and chemistry. Decades of being buried by fast food catalysed the Slow Food Movement which is described as “a cultural vision, a philosophy for living” and goes on to note that “in the age of machines, we want to celebrate something more human and kindle the artisan spirit in us.”

The mechanised, industrialised production of food and drink triggered the global artisanal movement where garagiste wine, craft beer, craft gin, farm-to-table vegetables and nose-to-tail butchers have sprung up all over the planet to fulfil the atavistic urge to consume that which was made by hand with care, craftsmanship, pride and passion.

This isn’t too surprising given the pejorative nature we attach to anything artificial. Artificial sweeteners. Synthetic fabrics. Fake news. Ersatz coffee. Imitation Picasso. Replica Rolex. You get the idea – anything whose authenticity is questionable is never going to acquire the status of “the real thing”.

The Human Touch

It’s probably too early to tell whether or not the increased incursion of technology into our lives that AI represents will result in increased embrace of said technology or rejection thereof. In all likelihood, whatever scenario we find ourselves in will inevitably involve a hybrid of the two. However the early signs are that – in South Africa at least – humans prefer the human touch.

With that simple insight in mind, I for one plan to continue writing my own articles and creating my own content. Sure, I will occasionally use ChatGPT as a consultant – much in the same way I regularly consult a thesaurus and a dictionary – but I will never use it as a replacement. This is not because I’m insufferably precious about my work but simply because I have a strong conviction that it isn’t something that meets any kind of human need. In the same way people would be less inclined to read a novel written by an algorithm as opposed to one written by a human, human instinct tells me that people would be less interested in reading an article burped out by a bot than one crafted by a professional writer.

In other words, I choose to see AI not as a rival intelligence but a complementary one. This is particularly the case when one’s occupation is writing, an art and a craft which involves sublimating opaque, elusive ideas into solid, concrete form. Creative writing relies heavily on one’s life experiences as a human and how one is able to express various aspects of the human condition in tangible, recognisable fashion. Sure, an AI can mimic this by producing writing of breathtaking verisimilitude to that of a human. However it can only generate it, not originate it; it can recreate it based on a billion data points but not create it from scratch.

Best Practice

In this regard, I am following what is increasingly being seen as best practice in the content creation profession, most recently articulated by HubSpot, one of the world’s leading software development companies. Whilst grappling with how best to incorporate the technology into their business practice, the HubSpot blog team collectively decided to “use AI to learn about topics faster, but we won’t use AI alone to create content.”

To invert the old padagogic axiom, an AI can be taught what to think but not how to think. Again, this must be qualified with the caveat: “yet”. Yes, the artificial brain can process information infinitely more quickly than the organic one, but it is still dependent upon the latter to tell it which information to process and to what purpose. It is analogous to a bomb that cannot light its own fuse: no matter how many marvels of engineering are inherent in the bomb, without external intercession it remains dormant and inert.

Quality / Quantity

Much of this has to do with the qualitative nature of thought as opposed to the quantitative component thereof. The computer brain can process more information at greater speeds than the human brain, but, unless given specific instructions, is incapable of determining what information to process and why. Left to their own devices, a human might quickly invent or create something. Without anyone to tell it what to do, an AI left to its own devices will achieve precisely nothing. When it comes to creativity, originality, inspiration, vision and acumen, the organic brain maintains a total advantage over the digital one.

Although it’s difficult to arrive at a pithy conclusion, I’m not trying to write a book here so conclude we must. I will rather shamelessly borrow from that vaunted publication The Economist and their recent issue on the subject. As the beautifully simple cover illustration demonstrates, the smart approach for us humans right now is to treat AI as both a blessing and a curse and navigate a course into the future where it will become more of the former and less of the latter. In a cunning turn of phrase that hedges our bets whilst remaining optimistic, us humans must learn how to “worry wisely about AI”.

Now read Part 2 of AI & I.

Keen on a quarterly slice of succinct insights from the inside track? Sign up to our newsletter.

Sign Up!